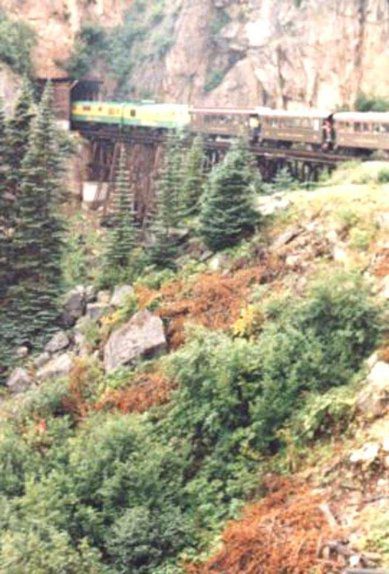

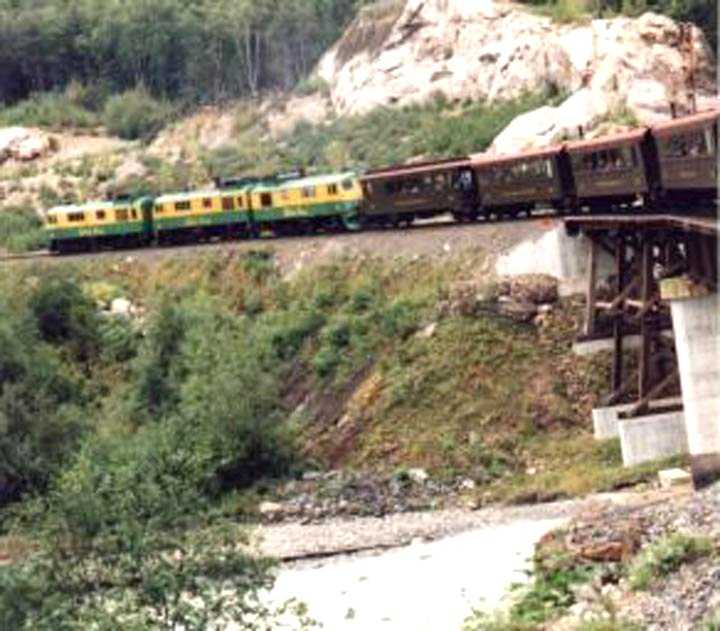

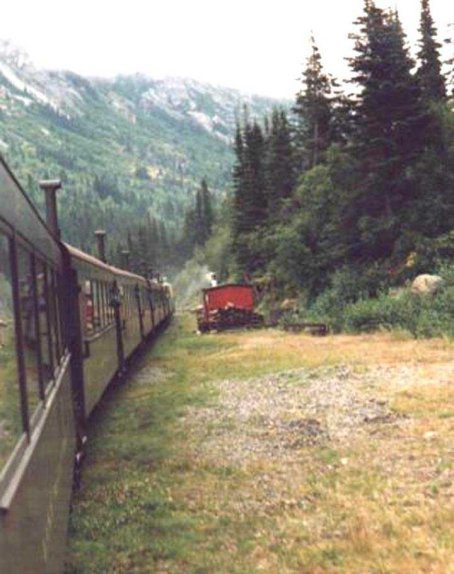

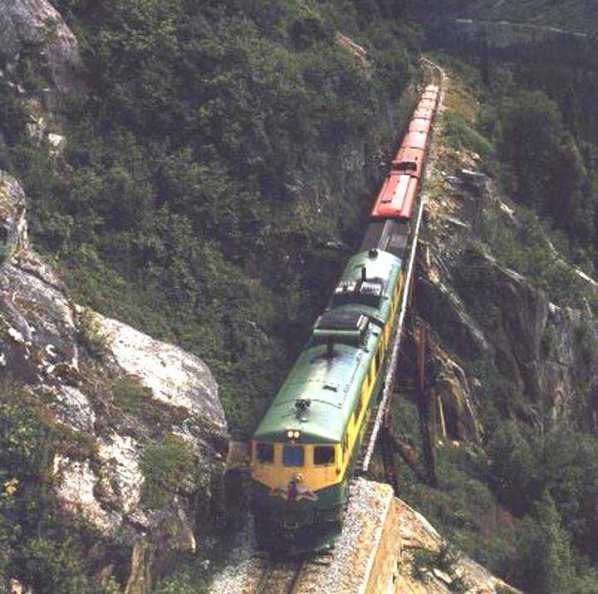

White Pass and Yukon Route railway, Skagway, Alaska

By Don Woodwell

It was on the Yukon River at Dawson (Yukon Territory) that gold was found in the 1890’s. When the first loads of gold were brought into Seattle in 1897, the gold rush stampede began. People from all over the U.S. flooded into Alaska seeking riches. For most seekers, however, the arduous 20-mile climb from Skagway at sea level up to the White Pass summit, and another 20 miles to Bennett at the head of the water route to the Klondike, was enough to discourage even the strongest wills. Since Dawson is another 550 miles from Bennett via a water route across Bennett Lake and down the Yukon River, miners still faced a rugged and demanding journey.

Captain William Moore, Skagway founder and visionary, predicted this rush for riches. Captain Moore surveyed a new route through the White Pass that was deemed easier and less steep than the Chilkoot Pass. Finding an easier way over the steep and treacherous coastal mountains was of great importance to the miners who walked with their equipment on their backs or prodded packhorses up the trail.

Skagway, situated at the top of the inside passage at the end of a 1,000 mile steamship journey from Seattle, was the perfect starting point for prospectors heading to the Klondike gold fields. Almost 20,000 prospectors and gold miners passed through Skagway over the White Pass summit to the town of Bennett. In order to enter Canada, Customs agents required that each miner carry at least a ton of supplies, enough for one year. This meant that miners often took 20 to 30 trips up and down White Pass mountain trails in order to get 2,000 pounds over the summit.

Early in 1898, two men came north intent upon solving the transportation problem over the coastal mountains. One was Sir Thomas Tancred, a representative of British financiers who sensed a business opportunity. The other was a Canadian railway contractor named Michael Heney.

Both Tancred and Heney surveyed the mountain route. Tancred concluded that it was impossible to build a railroad over the rugged coastal mountains to the White Pass, but Haney was convinced otherwise.

By chance Haney and Tancred met one night in a Skagway hotel bar. They talked through the night and by dawn the railroad project was no longer a dream but reality. Tancred and his financiers raised $10 million, and Haney built the railroad.

Organized April 18th, 1898, the White Pass and Yukon Route received its first shipment of supplies and construction began on a narrow gauge railroad. Narrow gauge was chosen for two reasons: the 3 ft. gauge of the track would only require a 10 ft. wide roadbed; and, narrow gauge track requires a small turning radius. The latter is extremely important in order to negotiate the tight curves of the White Pass canyon.

Construction started and within three months the first four miles of track were completed. The first engine started service over this limited right of way making the WP&YR the northernmost railroad in the Western hemisphere. From there on, though, the going got really tough. From Skagway, at sea level and milepost 0.0, the canyon climbs vertically over half a mile to the summit at White Pass at milepost 20.4 with grades as steep as 3.9%.

The first crews surveyed the route to the White Pass, and determined where the track would be laid. Next timber cutters cleared a passage. As many as 2,000 laborers at any one time hacked and blasted the route for the rail bed. Carpenters, engineers, and welders constructed tunnels and enormous bridges amid this grand landscape. It’s estimated that more than 35,000 men worked on the WP&YR construction at one time or another. Although a very dangerous undertaking, only 35 workers lost their lives.

Over 450 tons of explosives were used in the construction from Skagway to the summit. Workers often dangled in harnesses on the sides of 1,000 ft. high cliffs to drill holes for the explosives to blast a roadbed out of these sheer granite walls.

Not only the precipitous geography but also the weather was a major factor in the progress of railroad building. Heavy snows and temperatures as low as 60O below zero hindered the work. In the winter, men could work only one hour at a time in cold frigid weather.

In spite of the hardships, on February 20, 1899, they reached the White Pass summit. Four months later the railroad construction reached another 20 miles to Bennett (B.C.), the beginning of the river route to the gold fields at Dawson in the Yukon Territory.

The next challenge for Heney was to construct the railroad all the way to Whitehorse, 70 miles beyond. It was done in two stages: Between Bennett and Carcross; and, between Carcross and Whitehorse. Each segment was constructed with its own track gang. On July 29th, 1900, both track gangs met at Carcross where a ceremonial gold spike was driven by the company’s first president.

More than 3,000 ties imported from Oregon were required for each mile of track. In addition to blasting through the hard granite mountainsides, enormous bridges and tunnels had to be built. The most impressive was a steel cantilever bridge that spanned a wide canyon. It was the tallest in the world when built. Today it is still in its place but is no longer used as the trains became much too heavy during the Yukon mining days.

While locomotives were imported, the rolling stock was crafted locally. The WP&YR built its own freight cars and passenger coaches in their own shops saving them the cost of importing them. The machine shops allowed rail cars to be built with northern conditions in mind. The harsh environment meant that these railcars must be sturdy but easily and quickly maintained by local crews.

Some crews built trains, others laid track, and still other teams of carpenters constructed a network of train depots, water towers, and coalbunkers. These specialized buildings assured the railroad’s reliable operation.

Maintaining the railroad was more challenging than anticipated. At the White Pass summit, 20-foot snowdrifts were common. Storms hit suddenly and lasted for days. A steam driven rotary snowplow mounted on the front of a train and handled by a 10-person crew ate a tight ten foot wide path through the massive amounts of dense Coastal snow. In the worst conditions, a second train would attack the snow from the opposite direction to assist in clearing a passage.

By 1901, many of the pick and shovel gold miner’s claims were consolidated by large corporations who gained control of ore mining in the Klondike. Concentrated copper ores were shipped by WP&YR sternwheelers on the river route to the railhead at Whitehorse and carried by train to tidewater Skagway. At the port, giant cranes lifted the ore into sea carriers for transport back to the warmer weather ports along the West Coast of the US and Canada.

During World War II, the railroad was the chief supplier for the U.S. Army’s Alaska Highway construction project. Steam locomotives were the primary power until 1954 when the railroad began purchasing custom built diesel electric locomotives from either Alco (Toronto) or GE. The railway matured into a fully integrated transportation company complete with modern container ships and highway tractor-trailers.

In 1982, world metal prices plummeted and major Yukon ore mines shutdown. The WP&YR also was forced to close that year, but not for good. Increasing numbers of cruise ship passengers visiting Skagway with hopes of sampling the Klondike adventure resuscitated the railroad. It opened in 1988 exclusively as an excursion train, and 14 years later it is still one of the most breathtaking excursion trips in North America.

The WP&YR was declared an international civil engineering landmark in 1994 putting it in the same class as the Panama Canal and the Eiffel Tower.

The restored depot in Skagway is well stocked with railway memorabilia, clothes, and model trains. Both Bachman and LGB provide models of WP&YR locos and rolling stock. You can order their products on http://www.whitepassrailroad.com/. This excellent site is worth your time to visit.

I recommend a fine book called “The White Pass and Yukon Route Railway” written by Graham Wilson and published in 1998 by Wolf Creek Books Inc., Whitehorse. Order this book through the railway’s Web page. The book is a compilation of many pictures and newspaper articles from the period as well as several narratives of the railroad’s construction and the transportation network it created.

An interesting video called “The Engineers View” is also available from the WP&YR depot. An engineer handling the controls of a GE diesel describes the rail journey from Skagway to Fraser.

The railway is a great source of modeling ideas for your own layout. On30 trains are 1/4 inch to a foot but run on HO track to approximate the WP&YR’s three-foot gauge. While it may not be possible to model the entire 20 mi. from Skagway to White Pass, many of the sections including the trestles, the spindly cantilever bridge, and the tunnels certainly could be included in our layouts.

For those of you who may be traveling to Skagway via a cruise ship, airplane, or the Alaska Highway, be sure to ride the WP&YR. The rugged mountain pass is no less difficult nor the scenery less spectacular today than when the miners tackled it on foot. Looking 800 feet down into the Skagway river gorge from the coach’s platform, you almost feel like the people who first rode the new railway one hundred years ago.