Association of American Railroads Teacher’s Kit – Part IV

Presented by Bill Fuller

In the early 1940s, the Association of American Railroads (AAR) offered a Teacher’s Kit for use in teaching public school students about the transportation industry. Of course, in the mind of the AAR, transportation equaled railroads, and the kit includes over 50 photographs of railroad scenes. Each photograph is accompanied by a descriptive story, each of which becomes a short history lesson in the place of railroading in American culture and economy. A complete copy of the original kit is in the archives of the High Plains Western Heritage Center, Spearfish, South Dakota. Its contents have been scanned and reprinted for public viewing in the Heritage Center by TCA member Bill Fuller, who has also provided a copy to e*Train. Each new issue will feature one of the photographs and its story

The “East and West Railroad” or “E & W” shown in the photographs never existed. Actual railroad names were replaced in the photographs probably to avoid the appearance of giving free advertising to some railroad lines while slighting others.

What is the Association of American Railroads?

The 1941 – 1943 Teacher’s Kit containing these photographs and descriptive text was published by the Association of American Railroads (AAR). The following information about this organization is quoted from the AAR Web sites http://www.aar.org/About_AAR/aar_history.asp and http://www.aar.org/About_AAR/about_aar.asp, retrieved November 23, 2004:

The AAR was formed in 1934. But its history really goes back much further–all the way to 1867 when the Master Car Builders Association was formed to conduct experiments aimed at standardizing freight cars.

Soon other organizations representing other railroad subjects were formed. By the early 1930s, there was an alphabet soup of organizations representing the industry. Included were the Association of Railway Executives, the American Railway Association, the Bureau of Railway Economics, the Railway Treasury Officers Association, the Railway Accounting Officers Association and the Bureau for the Safe Transportation of Explosives and other Dangerous Articles. These and others were folded into the new Association of American Railroads, when it was established on October 12, 1934.

The unification of rail associations was a fallout from the Great Depression. In 1933 the Rail Transportation Act was passed and a Federal Coordinator of Transportation was appointed to deal with depression-era problems affecting railroads. Beset by a plethora of voices representing the railroad industry, Coordinator Joseph B. Eastman – with the support of President Franklin D. Roosevelt – soon recommended that railroads unify into one organization that could speak for the entire industry, leading directly to creation of the AAR.

AAR members include the major freight railroads in the United States, Canada and Mexico, as well as Amtrak. Based in Washington, DC, the AAR is committed to keeping the railroads of North America safe, fast, efficient, clean, and technologically advanced. Much of the AAR focus is on Washington, bringing critical rail-related issues to the attention of Congressional and government leaders.

The AAR is also very much involved in programs to improve the efficiency, safety and service of the railroad industry. Two AAR subsidiaries – the Transportation Technology Center, Inc., and Railinc – ensure that railroads remain on the cutting edge of transportation and information technology.

Railroads are the vital link to our economic future. More than 40 percent of all US freight moves by rail – more than from any other single mode of transportation. As Fortune Magazine recently observed, “While Internet companies scramble for sound business footing, many of America’s trains are running on Internet time – at a profit.”

© 2004 AAR 50 F Street, NW, Washington, DC 20001-1564 •• 202-639-2100

Used with permission”

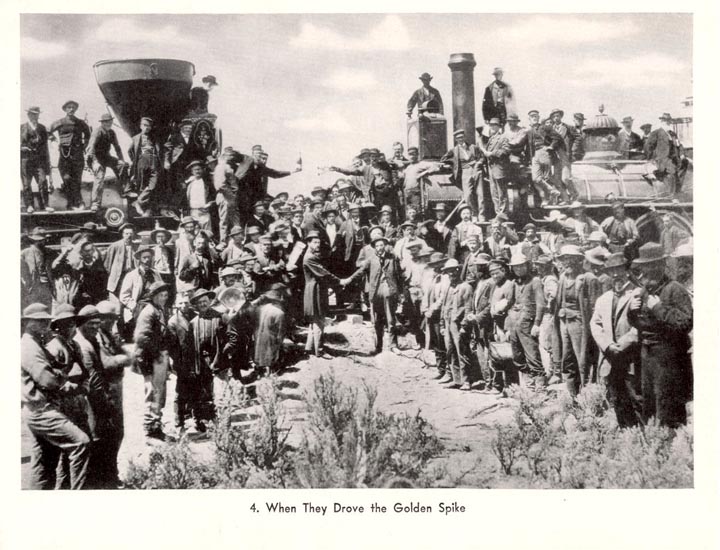

Story # 4

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 gave great impetus to the westward movement. IN the years that followed, while scores of railway lines were being pushed through the fast-growing Ohio and Mississippi Valley regions, thousands of gold seekers and other adventurous spirits were making their way by various routes to the new “El Dorado”.

May took passage on sailing vessels bound around “The Horn,” a hazardous voyage that required months. Many others went by clipper ships or steam vessels to the Isthmus of Panama, crossed fifty miles of jungle, and embarked on the other vessels bound for California—a journey of several weeks. Still others braved the perils and hardships of an overland journey on horseback, or by stagecoach, or covered wagon, across plains and deserts and over dangerous mountain trails. Fortunate indeed was the traveler who made the trip from St. Louis or St. Joseph to California in three or four weeks of strenuous travel.

In 1850, there was not a mile of steam railroad anywhere west of the Mississippi River.

The first locomotive to turn a wheel west of the Mississippi River ran out of St. Louis in 1852. At that time the talk of railroads was on nearly every tongue, and a few railroads were actually getting under way in the West. From St. Louis and Hannibal, Mo., and from Burlington, Davenport, Clinton and Dubuque, Iowa, railway lines soon began pushing westward from the Mississippi River.

Before the close of the decade 1850-59, several railway lines were in operation in Iowa and Missouri, and the “Iron Horse” had penetrated as far west as the Missouri River at St. Joseph. From 1850 to 1860,railway mileage in the United States increased from 9,021 to 30,626 miles. Ever since then this country had led all other countries in railway mileage.

Meanwhile, the country had been growing by leaps and bounds, with the railroads playing a major role. Many railroads were being built; other railway projects were in contemplation. One of these was a line of railroads, 1,776 miles in length, extending from the Missouri River all the way to the Pacific Ocean!

The proposed rail route would be two and one-half times longer than the longest railroad then existing in the world.

One day, in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln, sitting at his desk in the White House in Washington, signed a document that fixed the eastern terminus of the proposed rail route at Omaha, Nebraska Territory. In California, another company was organized to build a railroad eastward from San Francisco to meet the road from Omaha. Within a short time dirt was flying in Nebraska and California.

Thousands of workmen, large numbers of teams, many supply trains, and vast quantities of equipment and supplies were employed in carrying this stupendous project forward. Each month the gap between the two construction forces became shorter, and finally, on May 10, 1869, after six years of strenuous effort, the rails were joined at Promontory, on the Utah desert.

A train from the East and a train from the West, each bearing a distinguished passenger list, approached and halted within a few feet of each other. Then, between the noses of the two locomotives, a memorable scene was enacted. In the presence of many notables who had come by train and hundreds of workmen, the last spike—a spike of pure California gold—was driven, signalizing the completion of the first chain of railroads to span the American continent!

The driving of the golden spike in Utah on that eventful day marked an epoch in American history. It brought to an end the isolation of the Far Western country. It united and cemented the East and the West—brought the cities of the Atlantic and Pacific within a few days’ journey of each other. It opened up a vast region for settlement and development. It rendered unnecessary the perilous cross-country journeys by stagecoach or covered wagon or the long hazardous journeys by water around Cape Horn or by way of Panama.