Lionel’s Textbook of Model Railroading

By Joseph H. Lechner

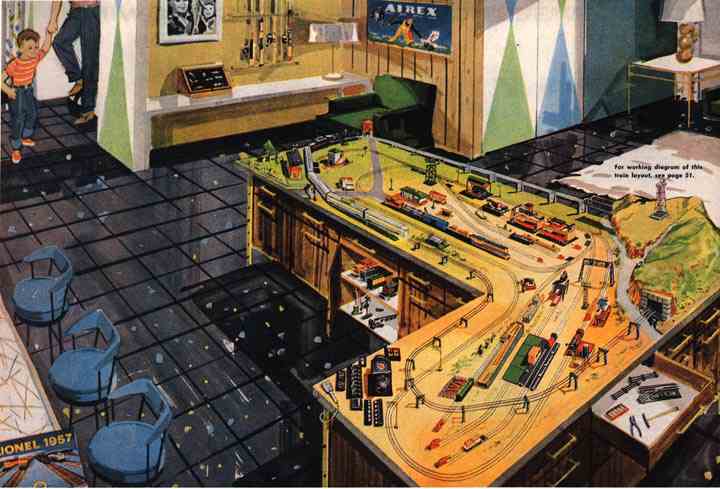

Lionel’s 1957 consumer catalog has always been my personal favorite. It also happens to be the first toy train wishbook I ever owned, but I don’t think I’m prejudiced by that fact. The 1957 train line was bigger and better than any before or after it during the postwar era. Notable milestones for that year included Super “O” track, the Norfolk and Western “J” class 4-8-4, and the coveted Canadian Pacific passenger set. Equally attractive, in my opinion, were the Wabash GP7, the Milwaukee electric, and the first complete train of Budd RDC cars.

A postwar Lionel catalog was a thing of beauty and a joy to behold. Robert Sherman’s artwork brought each train set to life. When a new catalog came out in September, the first place we looked was those double-page spreads where Berkshires, GG1s and sleek Alcos roared by larger-than-life. Even a lowly 2-4-2 became fascinating when Sherman posed it with a long train in a detailed landscaped setting. Eventually, sated with the newest in steamers and diesels, we would turn to the back pages that described the old, the familiar and the mundane. Straight track, 8 7/8” long; twenty-five cents per section. And don’t forget a Lockon and some 18 gauge hookup wire.

But wait, there’s more. The 1957 edition offered something special, unlike any Lionel catalog before or after it. Its last four pages were a veritable textbook of model railroading: a step-by-step guide for turning a starter set into a dream layout like the one you saw in the toy department at Wanamaker’s.

Sure; every toy train catalog had a page of track plans in the back: buy twelve curved tracks, four straight tracks and a 90° crossing; assemble as shown to make a figure-8 that measures 27” x 54”. However, this catalog did something that no other catalog did before or after: it showed how to grow a simple loop into an empire; and it provided inspiring full-color artwork to show what the finished result would look like.

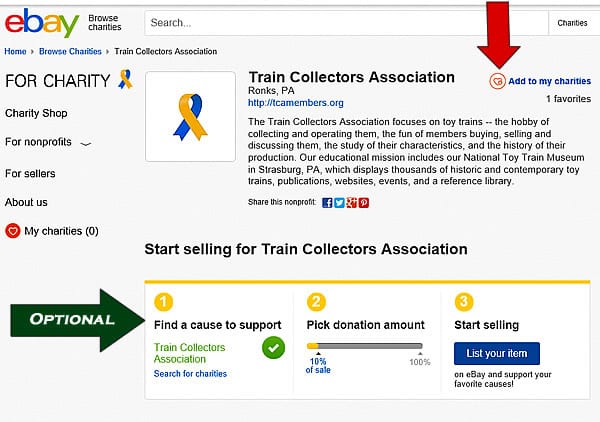

Demographics collected by The Lionel Corporation suggested that the recipient of a train set was likely to be a boy between the ages of 8 and 12; that he would add cars, track and accessories for the next five years; and that most of the purchases would be made on his behalf by female relatives. Lionel’s 1957 issue stands alone as a masterpiece of marketing. It showed the young railroader how to expand his layout; it showed mothers, aunts and grandmothers what items he’d be needing next; and it all but invited a series of return visits to the local Lionel dealer.

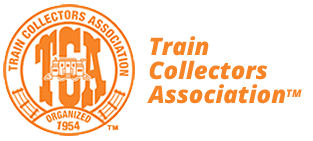

The lesson began with a modest 027 train set: number 1585W, pulled by the #602 Seaboard diesel switcher. Its only luxury was a battery-powered air horn; but with nine freight cars, this set made history as the longest train ever cataloged by Lionel. A banner proclaimed the “brute strength of the new 600 series” that enabled these diesels to pull longer trains than ever before. Actually, #602 wasn’t more powerful than its predecessors; instead, its cars were lighter. Seven of the nine cars rolled on new-in-1957 Timken plastic trucks.

“Isn’t she great!” gushed the catalog, recounting the joys of transformer-controlled forward and reverse, sounding the horn for imaginary grade crossings, and turning down the room lights to better appreciate #602’s working headlight. But running around and around a loop of track could get old; this generally happened at about the same time the Christmas tree came down and the fragile glass ornaments got packed away in the attic. Time to visit a Lionel dealer for more track and some accessories.

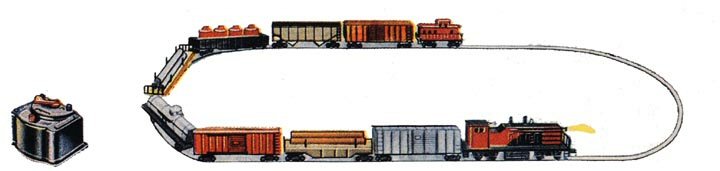

After acquiring a train set, one of the first additional purchases was a pair of switches. At least, that’s what toy train catalogs called them. Real railroads called them turnouts; scale model railroaders called them turnouts; but Lionel always called them switches. Depending on how they were arranged, a pair of switches could either (a) provide a new route for the train to travel, or (b) open up sidings where cars could be loaded and unloaded.

You can tell a lot about a person’s psyche by the way he or she operates a train. There are kinesthetic types that want to keep a train barreling down the track at 120 scale miles per hour, blasting the horn at every crossing; a Type A personality needs a type (a) layout. Then there are the thoughtful, contemplative types who are content to spend hours spotting a #6342 gondola at exactly the right position for the #345 culvert unloader; the Type B railroader wants a type (b) layout. The two-switch layout shown here just might be the most common add-on track plan in the toy train universe, because it satisfied both personalities. I ought to know; I received the exact same layout for Christmas at age six. You could use the back track for industrial switching, as the drawing demonstrates; or you could use that track as a second route for the train, preferably not while the gondola was still being unloaded. This particular track plan was also very popular because the layout, consisting of eighteen straight tracks, ten curved tracks and a pair of switches, would fit on one 4×8 sheet of plywood.

Simple accessories that made this layout interesting included a #133 station, a #71 lamp post, a #252 crossing gate, and a #494 rotating beacon. I think it’s significant that a small-town depot was the first scene developed on this layout. #133 is a model of the quintessential station in Middle America where Dad took Junior to see trains. For most of us, a clapboard depot was our port of entry to the world of railroading, whether we boarded a Pullman there to begin a journey, or else we merely hung out there to watch. To reach the depot, we rode in the family auto; and it bumped over the tracks at a crossing that was guarded by a gate like #252. Usually, our first notice of a train’s impending arrival was flashing red lights and the silent lowering of the black-and-white striped gate. If we waited for the train at night, the platform was well illuminated by tall iron lamp posts like #71.

The remaining accessory, #494, relates to yet another form of transportation, the airplane. Placing an aircraft beacon on your layout was significant because it indicated there was a world out there beyond the confines of your plywood table. It also indicated that your layout was modern and sophisticated enough to boast the latest in aviation technology. Every six-year-old Lionel owner knew that those little red and green caps with the concentric circles on them were called Fresnel lenses. But I was in my forties before I learned that Augustin Fresnel was a nineteenth-century French physicist who pronounced his name “Fren-NELL”. Youngsters in the 1950s related to #494 because they had all seen beacons just like it at the local airport. In 1957, the airport had become the new location for male bonding; a place where fathers and sons flocked to see the Douglas DC-7, the Lockheed Electra, and perhaps the new Boeing 707. Ironically, aviation diverted the public’s attention away from railroading, a trend that would soon bring about the demise of passenger service and nearly terminated the toy train industry in the mid 1960s.

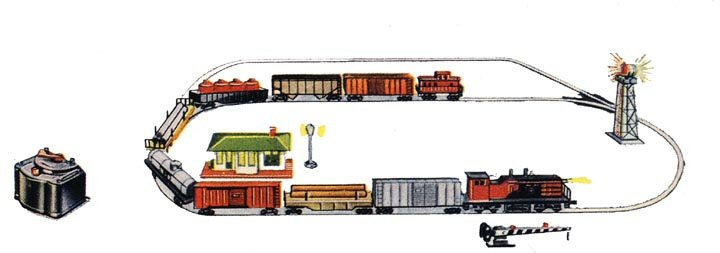

Lionel’s marketing magic was working. The lucky recipient of set #1585W (or more likely his mother, aunts and grandparents) have made several return visits to the dealer. Junior selected his second train from the very 1957 catalog that came with his Seaboard switcher. It’s outfit #2276W, a commuter train pulled by the #404 Budd RDC-4. This addition greatly increased the variety of the layout; now he could transport both passengers and freight. But wait, there’s more than meets the eye.

Once Junior brought home his new Budd set, he was in for a surprise. #1585W was an 027 set, but #2276W was O gauge. Its tracks were longer, the curves were wider, the rails were taller, and the pins on O gauge wouldn’t fit into the narrower 027 rails. Those 16” long passenger cars couldn’t go around 027 curves; and even if they could, they’d look silly doing it. Welcome to the world of planned incompatibility. Our young railroader has decided to set aside his 027 track and replace it with the more durable, but also more expensive, O gauge track.

That diagonal track where the RDCs stood was a subtle jab at Lionel’s competition. As the caption pointed out, the siding also served as a reversing loop. The train had been running counterclockwise when it entered the siding at the back; it will be going clockwise when it re-enters the main line by the station. As Lionel was quick to point out, reverse loops were easy with three-rail track. They were hard to duplicate with American Flyer’s two-rail track, because the running rails would short out unless you added special wiring that Gilbert didn’t provide.

Junior soon made a second discovery: the little #1053 60-watt transformer that came with his Seaboard set couldn’t keep pace with a Budd set (with two light bulbs per car), a station, a crossing gate, a beacon, a culvert unloader, a semaphore, and two pairs of switches (with their total of twelve light bulbs). O gauge sets didn’t even include a transformer; so it was back to the dealer again for a larger, 175-watt TW.

Right now, our young engineer runs one train and leaves the other parked. He’ll soon make a third discovery: it’s impossible to keep both trains running continuously on this layout. Once he realizes that, it’ll be back to the dealer for more track, more switches—and this time, a KW or ZW transformer that will let him control both trains independently.

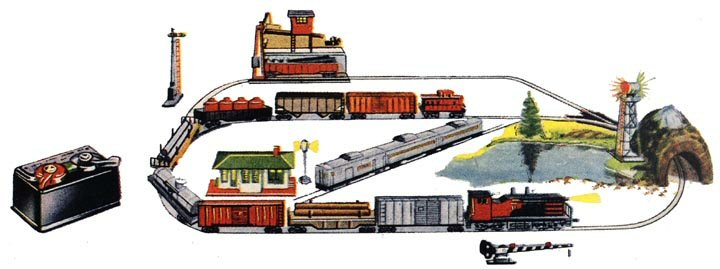

Lionel’s textbook of model railroading shows how a bare table top becomes more interesting when it’s landscaped. The branch line runs past a lake; the main line passes through a tunnel; an aircraft beacon atop the mountain points to a bigger world beyond the edges of the train table. Plywood surfaces have now been covered with realistic textures: grass, gravel, and trees.

Some of the landscaping was Lionel merchandise, and some was not. Lionel sold ready-made tunnels, but also offered a #920 scenery kit that included tunnel portals. The lake was homemade; catalog copy said it was a mirror. Other toy train publications of the 1950s recommended glass, painted on the underside with blue and white streaks, to represent water. Lionel didn’t offer model trees. Life-Like did; however, popular hobby books of that era explained how to make your own trees from wire and lichen.

A generation ago, scale model railroaders might have dismissed that table-top tunnel as toylike. But more recently, the two-rail DC branch of our hobby has discovered that viewblocks make train operation more fun by increasing the apparent distance between stations. Today it’s quite common to see an HO or N layout with two towns on opposite sides of a 4×8 layout. Since you can’t see both towns at the same time, they could be miles apart. Often, the train passes from one scene to the other via a tunnel no bigger than Lionel’s #131.

Lionel’s 1957 catalog stands alone as a masterpiece of toy train marketing. This unique sequence of illustrations entertained, inspired, and sold products by showing how one hypothetical customer assembled his first layout using Lionel equipment.

What ever became of that young railroader? As his collection grew, he dismantled the 4×8 and went on to build the magnificent 9’ x 14’ layout featured on the back cover of the catalog. But, that’s another story for another issue.