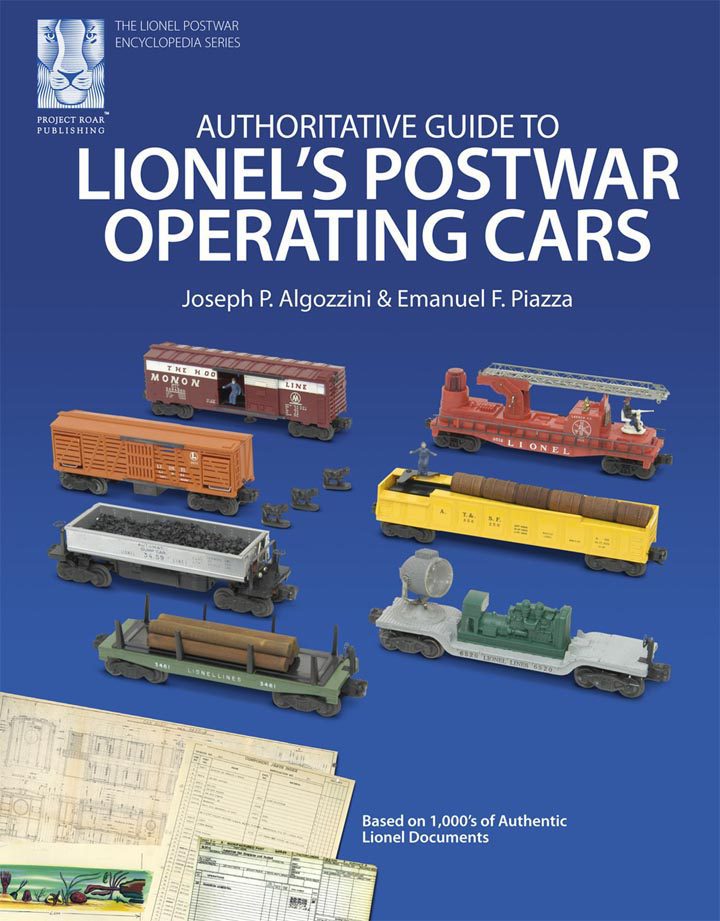

Authoritative Guide to Lionel’s Postwar Operating Cars

by Joseph P. Algozzini and Emanuel F. Piazza. 2005: Project Roar Publishing. $44.95 (softcover); $59.95 (hardcover).

Reviewed by Joseph Lechner

This is the first volume in a planned Lionel Postwar Encyclopedia series. The word authoritative in its title is no hyperbole. Not only was this book written by two of the most knowledgeable Lionel collectors in the world, but they had access to an important source of information that most of us will never see: original production records of the Lionel Corporation. It is no exaggeration to state that this is the most scholarly work I have ever read on the subject of postwar Lionel trains. Algozzini and Piazza have studied thousands of actual Lionel blueprints, component parts, indices, production control files, and factory orders. A Component Parts Index is a list of every part (including packaging) that is required to manufacture a particular item—complete with the proper hyphenated Lionel part number for each component. A Production Control File includes a bill of materials as well as explicit assembly instructions. A Factory Order is an instruction sent to the manufacturing floor that specifies what item(s) to produce, how many, and when the product is required.

The following example will serve to illustrate the thoroughness of the authors’ research.

One of the first new operating cars to liven up postwar freight sets was the #3464 animated box car, introduced in 1949. Previous boxcars were equipped with sliding doors, which a youngster could open to place loads inside. But #3464 opened its door for you by the magic of remote control! When you pressed the button to energize a magnetic uncoupling track section, the electromagnet pulled down a plunger, which released a spring mechanism that threw open the door, while a miniature man stepped forward! According to Lionel executives, nothing could be more satisfying to a youngster than to cause miniature adults to go to work on command.

Lionel produced ten different animated boxcars during the decade 1949-1958. Most hobbyists know that the boxcars themselves came in two different sizes. Fewer realize that the little blue men inside the cars also came in two sizes, with no obvious correlation to the car’s size. What Algozzini / Piazza call a “Type I” man stood 1-5/16” tall and held both arms upraised. The slightly smaller “Type II” man was only 1-3/16” tall and had only his right arm raised.

#3464 was 9-1/4” long and was available in tan with white New York Central lettering (#3464-1) or orange with black Santa Fe lettering (#3464-50). Both of these road names were available from 1949-1952. The authors suggest that two road names were produced so that each #2333 F-3 could have its own matching boxcar. I had never thought of that before. #3464s always came with a Type I man; but his hands and face were painted pink in 1949-1950 and were left unpainted in 1951-1952. The #3474 Western Pacific “feather” car had a Type I man when introduced in 1952, but carried a Type II man in 1953.

1953 marked the introduction of 10-1/2” long “scale detailed” boxcars, including the first 6464 series cars as well as the highly realistic Tuscan-red #3484-1, lettered for the Pennsylvania Railroad, with a Type II man inside. The orange #3484-25 ATSF car, added in 1954, came with a Type II man that year, but carried the taller Type I man in 1955-1956. ATSF employees always came with painted hands and faces, while all Pennsy personnel were unpainted. Go figure.

The animated boxcar’s catalog number changed to #3494 in 1955 with the introduction of #3494-1 in the red / gray New York Central “Pacemaker” scheme. Algozzini / Piazza claim that the new number indicated a multi-color paint scheme. #3494-150 Missouri Pacific (1956) and #3494-275 BAR (1956-58) certainly lived up to that expectation; but then #3494-625 (1957-58), one of the most realistic and hard-to-find postwar Lionel freight cars, must have been the result of a cost-cutting measure that demoted it to all-Tuscan-red paint and all-white lettering. #3494-275 came with a tall man in 1956, but with a short man thereafter. The scarce and desirable #3494-550 Monon and #3494-625 Soo Line both carried short men with painted features.

And so it goes, as the authors tell the stories of dozens of operating cars made by Lionel between 1946 and 1969. (Space and military cars are not included; they will be covered in a subsequent volume.)

Authoritative Guide to Lionel’s Postwar Operating Cars includes price and rarity information for each car / accessory. Rarity is rated on a scale from one to ten. Although the authors sometimes refer to “current supply”, their rarity scale appears to be based mainly on Lionel Corporation records of the number of pieces originally manufactured. R1 means over 150,000 were made; R10 means 250 or fewer were made, which nearly always means a prototype, color sample, or factory error.

But Algozzini and Piazza know more than they are telling us. Their R system is interesting, but I would rather know the actual production figures on which the Rs are allegedly based. The authors tease us by presenting (on page 10) a sampling of the original Lionel documents from their collection. This photo-montage includes a blueprint, a component parts index, and a factory production order. Two sheets of paper near the center of the page immediately caught my attention. They are typewritten lists of the cataloged train sets manufactured by Lionel in 1957 and 1958. I learned that by far the most numerous train set offered in 1957 was the #1569 four-car freight, powered by a #202 Union Pacific Alco (75,000 pieces). In second place was the #1573 five-car freight led by a #250 red-striped steam locomotive (40,000). The smallest production run that is visible on the page was the #1578S passenger set pulled by a #2018 steamer (4,500). The rest of this list is tantalizingly covered over by other documents. Come on, guys, how many #2296W Canadian Pacific sets were manufactured?

On the portion of the 1958 list that is visible, by far the smallest production run was outfit #2502W, the Super “O” Budd RDC set pulled by #400 followed by one each of #2550 and #2559. This explains the baffling observation that Lionel’s non powered #2550 baggage-mail car has long commanded higher prices than either the #2559 coach or the powered #400 and #404, both of which should be intrinsically more valuable. #400 sold well as a motorized unit when it was introduced in 1956. Outfit #2276W from 1957 included a #404 and two #2559 coaches. The elusive #2550 appeared only in set #2502W, of which only 600 were made! #2550 was also listed in 1957-1958 catalogs for separate sale, but how many people would buy a second baggage car when their train set already includes one?

There is obviously a wealth of quantitative Lionel data residing in John Schmid’s basement. Joe and Manny, you are sitting on a treasure chest; please give the train collecting fraternity actual production statistics in your future works!

As mentioned earlier, this volume is the first in what promises to be a fascinating series. The next two releases will explore Lionel’s cataloged sets (1960-1969) and its promotional (uncataloged) sets from the same era. Get ready for some fascinating and enlightening reading.